Babi Yar (Babyn Yar): Tragedy and Truth

On April 27 and May 11, 2023, Sinai Free Synagogue presented a two-part program on Babi Yar. You can watch the recordings by clicking here: Part I and Part II.

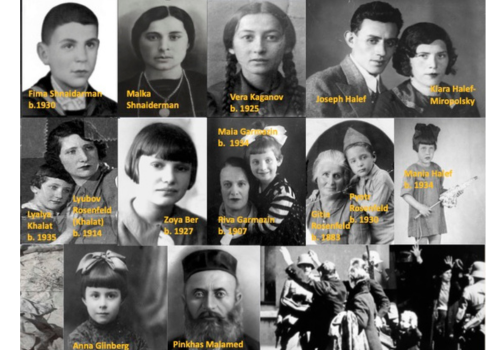

Picture: Some of the 33,771 Jewish adults and children murdered by Nazi mobile killing squads (Einsatzgruppen) at Babi Yar, a ravine on the edge of Kyiv September 29-30, 1941

The ‘Hidden’ Holocaust. The Holocaust usually brings to mind the death camps of central Europe. But it actually began on June 22, 1941 – over six months before the first Jewish transport to Auschwitz (where most Western European Jews were sent). That is when Germany invaded the Soviet Union. By the end of 1942, two thirds of all Jews murdered in the Holocaust had already died. They were the Jews of Poland and the Soviet Union, and they were killed either in mass shootings or in camps – Sobibor, Treblinka, or Belzec – located in German-occupied areas of Poland and the Soviet Union. Babi Yar was one of the largest mass shootings. And although it has since become “the single most symbolic site of the Holocaust in Ukraine and across the former Soviet Union,” Babi Yar is still unfamiliar to many people. Why is this so?

Part I: The Erasure of History

This was the first program in a two-part Zoom series about Babi Yar, the ravine (“yar”) on the outskirts of Kyiv where Nazi mobile killing squads (Einsatzgruppen) shot over 33,000 Jews on September 29-30, 1941, three months after the German invasion of the Soviet Union on June 22. One of the largest mass shootings of Jews in occupied Europe, it took place well before the first Jewish transport to Auschwitz, where most Western European Jews were sent.

While Babi Yar was the first “major massacre” of Jews in the Soviet Union, every city and town in Ukraine had “its own little Babi Yar.” Roma, Sinti, and other groups were also murdered. These systematic executions marked the start of the Holocaust; by the end of 1941, one million Jews had been murdered in eastern Poland and the Soviet Union – equivalent to the total number killed at Auschwitz. Yet in the decades to come, little was known about what French priest Fr. Patrick Desbois calls the “Holocaust by Bullets.”

This presentation described the tragedy’s historical context, which includes the Holodomor (“death by hunger” – Stalin’s man-made famine to force collectivization) in 1932-1933, and the Soviet attempt to suppress the memory of Babi Yar and deny that its victims were overwhelmingly Jewish. The denial arose primarily from two factors: historical anti-Semitism, and a political need to promote Soviet unity by claiming that all citizens suffered equally during the war. Jewish suffering must not be made special.

Many Jewish artists and writers bravely sought to reveal the truth, including the Jewish Ukrainian composer Dmitri Klebanov, who wrote the Symphony No.1 In Memoriam to the Martyrs of Babi Yar (1945); members of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee; and Yiddish poet Ovsey Driz, author of Lullaby to Babi Yar (1953), which was set to music by Rivka Boyarska and sung by Nechama Lifshitz.

Part II: Piercing the Soviet Wall of Silence

This was the second program in a two-part Zoom series about Babi Yar (Babyn Yar), a ravine (“yar”) on the edge of Kyiv, where Nazi killing squads (Einsatzgruppen) shot over 33,000 Jews on September 29-30, 1941, three months after Germany invaded the Soviet Union — and more than six months before the first Jewish transport to Auschwitz.

The invasion marked the start of the Holocaust. In the ensuing decades, Babi Yar was surrounded by an official wall of silence, which the Soviet regime maintained by means of censorship, imprisonment and worse. Its attempt to deny Babi Yar and the Nazis’ distinctly genocidal intent reflected two primary factors: historical anti-Semitism, and a political need to promote Soviet unity by claiming that all citizens suffered equally during the war. Jewish suffering must not receive special attention.

This program focused on the Soviet wall of silence and how it was at last overcome. We consider possible reasons why, eighty years later, Babi Yar and the “Holocaust by Bullets” are still unfamiliar to many. By the end of 1941, one million Jews had been killed in eastern Poland and the Soviet Union – equivalent to the total number murdered at Auschwitz throughout the war.

For decades, many Jewish writers, artists, and musicians courageously tried to tell truth about Babi Yar. And in the 1960s, two non-Jewish Soviet authors succeeded in bringing Babi Yar to the world’s attention: Yevgeny Yevtushenko, whose poem Babi Yar (1961) created a sensation, both in the USSR and in the West, and inspired Dmitri Shostakovich to compose his Symphony No. 13 in B Flat Minor, “Babi Yar” (1962); and Anatoly Kuznetsov, who wrote Babi Yar: A Document in the Form of a Novel (1966). Kuznetsov grew up in Kyiv; at the age of 12, he began keeping a journal of his life during the German occupation. This became the basis for his book, which is “every bit the peer of the canonical works of witness” by Elie Wiesel, Primo Levi, and others.

Throughout this program, Yevtushenko and Kuznetsov speak in their own words. As Anatoly Kuznetsov so eloquently said: “However much you burn and disperse and cover over and trample down, human memory still remains. History cannot be deceived, and it is impossible to conceal something from it forever.”

In March 2023, Anatoly Kuznetsov’s book was reissued with a new introduction by the journalist Masha Gessen.

We are grateful to the Forward for providing information used in this presentation.

Supplemental Information

Below is information to supplement these presentations.

Babi Yar (1961), by Soviet poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko. It first brought the tragedy to the world’s attention. Recited in Russian by the poet. English translation by A.Z. Foreman (recited by the translator). A Yiddish translation was published in the Forward

Babi Yar: A Document in the Form of a Novel, by Soviet author Anatoly Kuznetsov. First serialized in the magazine Yunost (Youth) in 1966. Although heavily censored, Kuznetsov’s eyewitness testimony – based on his boyhood journal of the German occupation – was groundbreaking. At the time, media in the U.S. described it as the “full story” and the “truth,” with no mention of censorship

- 1967 edition. English translation by Jacob Guralsky, based on the censored version; woodcut illustrations by the remarkable Jewish Soviet artist Savva Brodsky. He illustrated numerous other works of literature as well

- 1970 edition. English translation by David Floyd. Published after Kuznetsov defected to the U.K. in 1969, it includes the material deleted by the Soviet censors, as well as new material added by the author. This edition is not illustrated

- 2023 edition. David Floyd translation, with an introduction by the journalist Masha Gessen

Kirillovsky Yar (1941), by Jewish Ukrainian poet Olga Anstei. This was the first poem to be written about Babi Yar. Kirillovsky Yar is a network of gullies and ravines that includes Babi Yar. Born in Kyiv, Olga Anstei was able to flee the city and survive

Symphony No. 1 In Memoriam to the Martyrs of Babi Yar (1945), by Dmitri Klebanov, a Jewish Ukrainian composer. Orchestra and date unknown. Conducted by Igor Blazhkov

Symphony No. 13 in B-flat minor, titled Babi Yar (1962), by Dmitri Shostakovich. Two recordings:

- Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester. Conducted by Thomas Sanderling. Babyn Yar commemoration ceremony in Kyiv (Kiew). October 6, 2021

- WDR Symphony Orchestra Cologne. Conducted by Rudolf Barshai. Recorded 2000. The orchestra was founded in 1947 by Allied occupation authorities. After a number of guest conductors, the first principal conductor (1964-1969) was Christoph von Dohnányi, later to become Music Director of The Cleveland Orchestra. His father, Hans von Dohnányi, was a lawyer in Germany and the brother-in-law of German Lutheran pastor Dietrich Bonhoeffer. Both men actively opposed the Nazis and were executed in April 1945. Their story is told in No Ordinary Men, by Elizabeth Sifton and Fritz Stern

Lullaby to Babi Yar. Yiddish poem by Ovsey Driz (1953), melody by Rivka Boyarska, sung by Nechama Lifshitz. This video of the song has disturbing images. An English translation of Driz’s poem is also posted on this website

Historical Context: The Holodomor (1932-1933). A famine created by Stalin to force the collectivization of agriculture in Ukraine and the Soviet Union and perhaps to suppress Ukrainian independence. The word means death (mor) by hunger (holod) in Ukrainian and Russian. If not for the brutality of the Holodomor, which desensitized people to the suffering of others, it has been proposed that the non-Jewish population might have responded differently to the slaughter of Jews during the Holocaust

- Jones (2019), a film based on the story of British journalist Gareth Jones, who fought to tell the world about the Holodomor (the film has some disputed content). It can be streamed or rented and may also be available at your local library

- Eyewitness accounts of the Holodomor by Gareth Jones, Harry Lang (labor editor of the Jewish Daily Forward), and others. Four of Lang’s articles in the Forward can be found here (two are abridged). The accounts by New York Times Moscow Bureau chief Walter Duranty, who denied the truth about the Holodomor, have since been “largely discredited”